Don’t be a Hero: The Key to Good Storytelling

Storytelling can be an incredibly powerful tool for any type of persuasion – sales, marketing, and yes… philanthropy. But there’s a common mistake we often make that can seriously limit our power to persuade.

Our brains love stories. Something actually happens psychologically when we hear a story versus a list of information or facts. We suddenly lean in. That’s because we can relate and understand story. We make a personal connection with the characters and the challenges they face. We ask ourselves, “what would I do in that situation?”

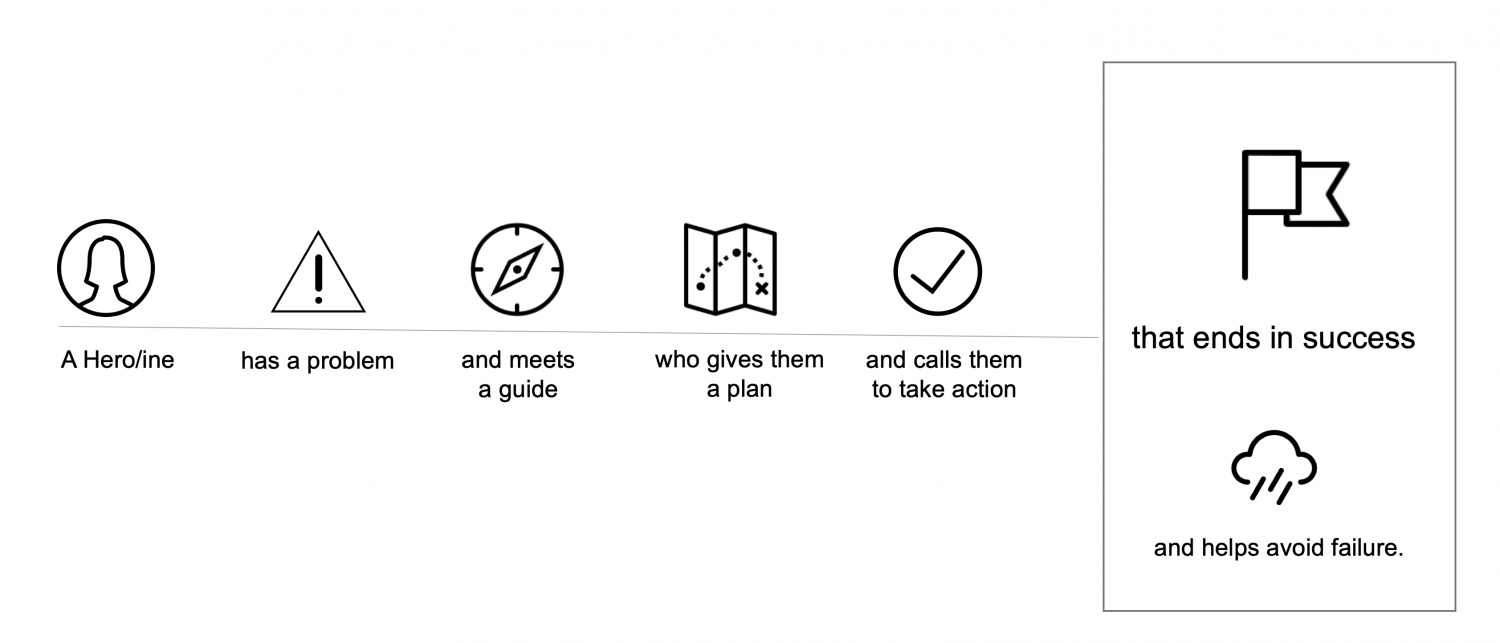

But the way we structure a story is very important in getting this reaction from our audience. Donald Miller has developed a tool called Storybrand, which points to a storytelling structure that’s been used for thousands of years. It exists in most of our favorite novels, movies, and Netflix series. It goes something like this:

Yoda helps Luke Skywalker use the force to become a Jedi and face his father.

Haymitch helps Katniss win the heart of the people and the sponsors she needs to be victorious in the Hunger Games.

Gramma Tala encourages Moana to sail across the sea and restore the heart of Tafiti and in doing so, become a way-finder.

But according to Miller, many of us make a serious mistake when using storytelling for persuasion – we don’t invite our audience into the story. The one thing you must keep in mind to avoid this tragic pitfall? You are NOT the hero – your audience is. You are the guide helping them win the day.

You’re not Skywalker – you’re Yoda. You’re not Katniss – you’re Haymitch. You’re not Moana – you’re Gramma Tala.

In philanthropy and higher education, we make this mistake all the time. It’s easy to do, because the work we do is… heroic. But, if you put yourself (or UGA) in the role of the hero, you haven’t left any room for your audience, and you’re sure to lose their attention quickly. Let’s look at an example:

“The University of Georgia is removing barriers and opening doors through the Georgia Commitment Scholarship Program. Our goal is to reach 400 scholarships by the end of the Commit to Georgia Campaign. Give today, and help us change the life of a deserving student.”

In this scenario, UGA (the hero) is asking the audience (the guide) to give (plan of action) so we can change students’ lives (win the day).

There are a few issues here. First, we are asking the audience for help to solve our problem. That puts us in a place of weakness, and no one wants to help a sinking ship. Secondly, no one wants to be the helper of the story, they want to be the hero. I’ve got my own problems to solve and days to win – good luck with yours.

Let’s try it a different way:

“You can change the life of a deserving student. Give today, and join hundreds of others in removing barriers and opening doors through our Georgia Commitment Scholarship Program.”

Now we are inviting them into the story. Our audience (the hero) can change lives (win the day) through giving to the GCS program (plan of action) provided by UGA (the guide). Much more motivating for the audience.

So, take a moment and think about the stories you are telling. How can you structure them in a way that your audience can win the day? The most heroic thing you can do is not be the hero.